The banners come out from their dusty corners, tarnish is scrubbed off from old medals and accolades sprayed from lip to lip: “Another icon dead,” without even knowing the meaning of the word.

The banners come out from their dusty corners, tarnish is scrubbed off from old medals and accolades sprayed from lip to lip: “Another icon dead,” without even knowing the meaning of the word.

In a society where art is relegated to tiny backroom parlours and the artist forced into subservience to earn a living and feed family, working at jobs other than his or her chosen calling is symbolic of the future of a lost country. Any nation that does not recognize its origins through the creative pursuits of its people is doomed to repeat its demented history for coming generations.

Already, our art, harassed by exterior forms and patterns, gropes blindly in a bright sunlight to find a firm foothold in its country of birth, if only to survive. We give lip service to mediocrity and denigrate our heroes, our leaders, political or otherwise, stalwarts who, in their lifetimes, brave the currents to defend a unique heritage. Yet we continue to strum a morbid soliloquy on the occasion of deaths, forgetting the dash between date of birth and hour of passing. A lament without remorse, as if to show face with the dead who can no longer hear the praise and let it be known to the whole country in gusty chants of, “How great thou art!”

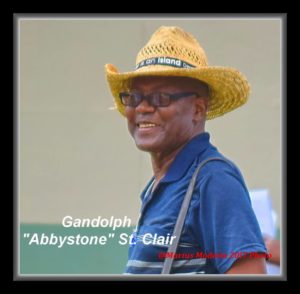

I first met Gandolph in the seventies in Vieux Fort. The place was a hive of activity then, with Halcyon Days in full swing and clients milling in and out of the several watering holes and nightclubs that mushroomed all over the small town. If you missed anyone in Castries who had not yet gone to New York, you only had to go by Sapphire Club, Cloud’s Nest or Kimatrai Hotel — guaranteed, you would find them called to the bar at one of these spots. Gandolph and I preferred the less exotic places and we bounced up upstairs J.Q.’s on Commercial Street or at St. Priscilla’s on Clarke Street, where the atmosphere was more conducive to our conversations. He was a budding musician at the time, had discovered the poetry of Walcott, and was writing lyrics and composing music. It was unusual to have met someone his age with such high ideals and indiscriminate taste in art, but when I learnt that he was a nephew of Mr. Mathew St. Clair, the famed headmaster of the R.C. Boys’ School in Castries, and had lived with him during his formative years, I understood.

In 1973 I published my first collection of poems, ‘Pebbles’. The proceeds from sales were given to the Government of Saint Lucia to go towards the building of a National Theatre. I remember Gandolph telling me that he was moved to write poetry when he learned of my gesture. Our paths veered, in and out, over the years, both of us having left the country at different times; but whenever we met the occasion was usually filled with anecdotes of an earlier life. He mulled over his struggles to maintain his status as an artist in this society, forced to eke out a living in far flung disciplines, remote from his true calling, with a calm humility that belied the raging torrent underneath that veneer.

In 1979 Gandolph left for Jamaica to attend the Jamaica School of Drama where he majored in directing before returning home. The impact of formal education and the Jamaica Experience was perhaps most pronounced in his music and avant-garde poetry. Kendel Hippolyte, renowned Saint Lucian dramatist and poet, commenting on Gandolph’s collection of poems, ‘Reaching Out’ had this to say: “He is fascinated by words, clearly. Their possibilities intrigue him, bemuse him virtually in the making of a poem, as it were. This fascination is reflected (refracted?) in a strong inclination for punning and word-coining.”

We were fortunate in 1984 to be asked by Derek Walcott to act in ‘Haytian Earth’, his play on the Haitian revolution commissioned by the Government of Saint Lucia to celebrate 150 years of Emancipation. I played Christophe to Gandolph’s Dessalines. Another outstanding Saint Lucian actor, Arthur Jacobs, portrayed Toussaint. It was more than ten years that I had last appeared on a stage, but under the guidance of the meticulous craftsman himself, and in such noble company, forgotten skills bloomed, albeit briefly. Gandolph’s performance was lauded by almost everyone who saw him. Kennedy Boots Samuels, in a review in the Voice of August 18, 1984, wrote: “I found Gandolph St. Clair brilliant in the performance. His down-to-earth Creole obscenities and his uneducated smiles at the right moment warmed the audience to him.”

Almost similarly, Adrian Augier in the Voice of August 11, 1984, observed: “ . . . the final condition of megalomania and tyrannical excess were best portrayed in the more gradual character degeneration of Dessalines, played by Gandolph St. Clair: certainly the strongest performance of the evening and a credit to his professional training.”

My knowledge of music beyond simple appreciation is zilch so forgive if I fail to remark on his virtuosity in this field. However, he was not a mere dabbler in that field and collaborated with other notable Saint Lucian composers like Charles Cadet and Mervin Wilkinson to produce such memorable pieces as ‘Let’s Start a Revolution’ and ‘Love Me’ that were quite popular in their era.

Gandolph invited me in 1984 to write the foreword to his eclectic work ‘Urf Song’. I wrote then, while I found at the time it was an honour, I had by then succumbed to society’s wishes, ceding my natural aptitudes and skills to the role of banker which was at least more ‘respectable’ and definitely rewarding. I approached the foreword with temerity and a lot of hope:

“I cannot help but recall the sixties when writers like Robert Lee and myself were braving the unknown in the spate of overwhelming criticisms from our friends who thought of us simply as mad fools to dare alter a fixed course that was carefully prepared from Royal Crown Readers, Nelson and Cutteridge texts and good old English Literature to write of breadfruit trees and sugar cane instead of poplars and maple. To see our people through eyes of understanding rather than a few natives on a beach waving palms to passing ships.

“Now, nearly 20 years after, [1964-1984] it is encouraging to observe a creative outburst of new St. Lucian writers flowing in their own peculiar lights, differing in styles and expressions from Adrian Augier, Kendel Hippolyte, Gandolph St. Clair to Portia Martial . . .”

If I appear to be rambling, it is because I wish to honestly preserve in living memory the benign spirit that was Gandolph. I am hard-pressed to ever remember seeing him angry, a perfect foil to the temperamental Sir Derek with whom he worked quite closely in later years. Gandolph played an active role in organizing creative events and in several impromptu and unofficial proceedings, especially when it came to welcoming friends of the arts from oversees. He was well known and respected throughout the Caribbean from Jamaica to Trinidad. I will miss his acerbic wit and mercurial talents. It can only be sincere in closing to quote the opening lines from Sir Derek’s Sea Canes in tribute to this long-serving Saint Lucian artist who sought no reward beyond an appreciation for his talents.

“Half my friends are dead.

I will make you new ones, said earth.

No, give me them back, as they were, instead,

with faults and all, I cried.”

Sea Canes by Derek Walcott.

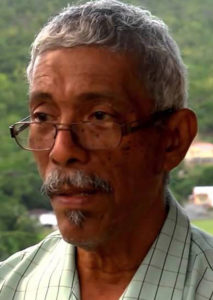

Besides writing and directing a number of critically acclaimed plays, Mc Donald Dixon is the author of three novels—Season of Mist (2000), Misbegotten (2009), and Saints of Little Paradise : Book One ‘eden Defiled’ (2012)—a collection of short stories—Careme and other Stories (2009)—and several volumes of poetry, the two latest being Beloved country and other poems (2013) and Collected Poems 1961-2001 (2003).

![]()