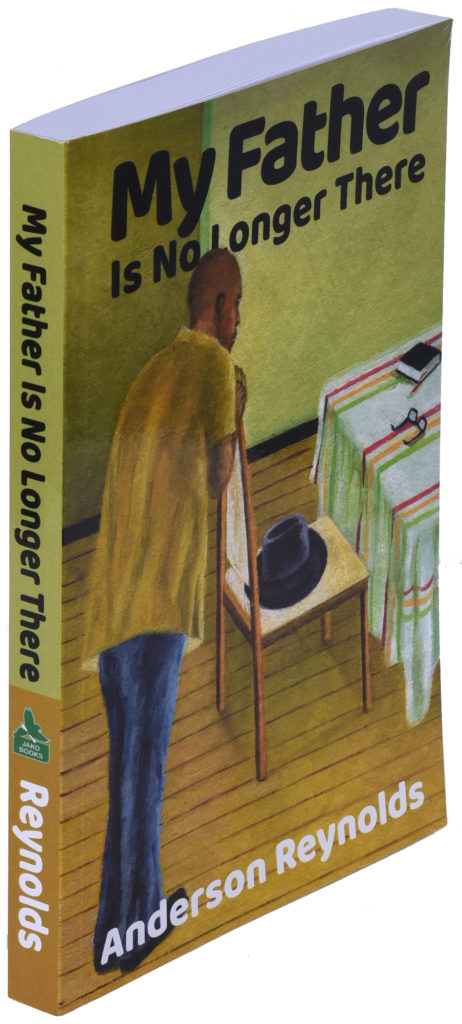

Among several works published by Saint Lucian writers in 2019– poetry, novels, history, biographies, memoirs – one of the most unique and moving was My Father is no longer There by Anderson Reynolds.

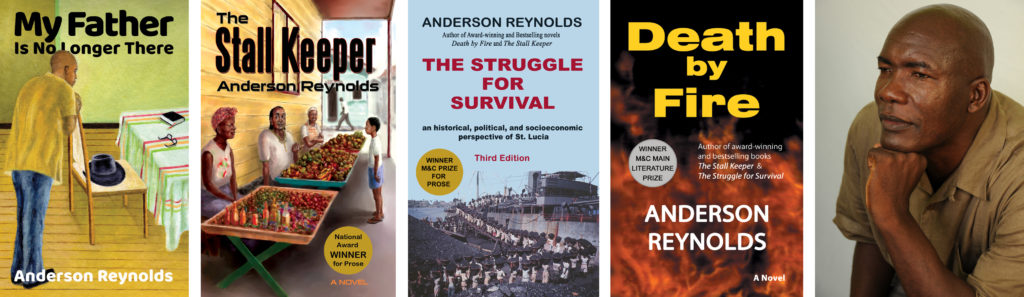

Reynolds has published two novels: Death by fire (2001), The Stall keeper (2017) andone work of non-fiction, The Struggle for Survival (2005.) He co-edited the short-lived literary magazine The Jako, manages Jako Productions and has published his books and those of a number of Vieux Fort-based writers under his imprint JakoBooks. An economist by training, he also manages musical groups out of Vieux Fort.

My Father Is No Longer There is a multi-layered text consisting of biography, autobiography, social history (covering farming, education, religion of rural Saint Lucia), memoir and confessional essay.

The 215-page volume is occasioned by the accidental death of his father. “On the wet morning of June 6, 2002, a car driven by a twenty-four-year-old motorist, spun out of control, ricocheted off another vehicle and plunged into my seventy-eight-year-old dad, who was on his regular morning walk alongside St. Jude’s Highway, on the outskirts of Vieux Fort, atown at the southernmost tip of St. Lucia.”The book and frank exposition which follow are rooted firmly in that opening sentence. The absurd accident, the Kafka-esque response of the insurance company, the coroner’s inquest, reaction of the family of the young driver, the writer’s bewilderment, lead into a searching examination of the meaning of his father’s life, his family experiences, their background in rural Saint Lucia,Reynolds’ becoming a writer.

The prose style and in particular the sections about his father, are excellent. A simple unadorned voice in which the strength of the first-person narrative, its emotional power (tempered by an objective searching out of what his family have experienced), provide a driving movement throughout the book that holds the reader’s interest.

Reynolds has given an incredibly detailed, closely observed account of his father’s life and the life of his family, including his own. Descriptions of farming (with a fascinating description of bee-keeping) school, religion provide a valuable record of the community he grew up in. In a chapter titled “A rendezvous with death,” he also probes, with a frank, confessional style, his reaction to his father’s sudden death, the old man now reduced to “a useless paper doll with dirt in his eyes, nose, and mouth.” His drive from Castries to Vieux Fort after he receives news of the accident, provides an opportunity to reflect on the island’s history, the immediate effect of sudden death of a parent and the way other people bring their own feelings to bear on the death of others.

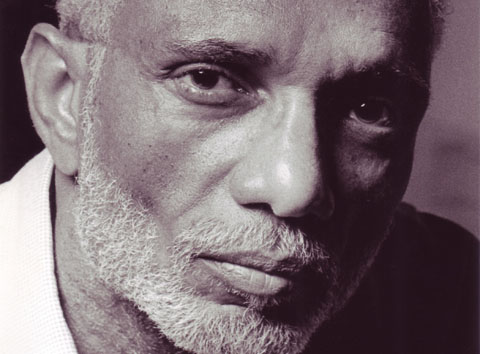

An illustrative addition adds poignancy to the memoir: a

grey-scale photograph of his father is placed at the beginning of each chapter,

and becomes clearer with each placing until at the end, the photo is the

clearest. An interesting symbolic support which still leaves the urgent

question,

“Who was my father” open, and possibly, unanswerable. How

much can memoir or biography really reveal about a life study?

This may well be the best literary work of Anderson Reynolds. It adds to the rich literary heritage of Saint Lucia, and indeed the Caribbean, with our shared cultures and histories. Given our shut-in situation these days, I recommend we add this book to the Saint Lucian literature we are catching up on.

John Robert Lee is a Saint Lucian writer and editor. Hislatest collection of poetry, “Pierrot” is published by Peepal Tree Press, 2020.

An Interview with Dr. Anderson Reynolds

![]()