by Alexander Clarke and Dr. Anderson Reynolds

Taiwan recently pledged EC$5.4 million to help fund St. Lucia’s youth economy initiative, suggesting that the Labor Party’s 2021 election and manifesto pledge of building the youth economy wasn’t just a campaign gimmick or a substitute for not having a credible and inspiring vision for the country.

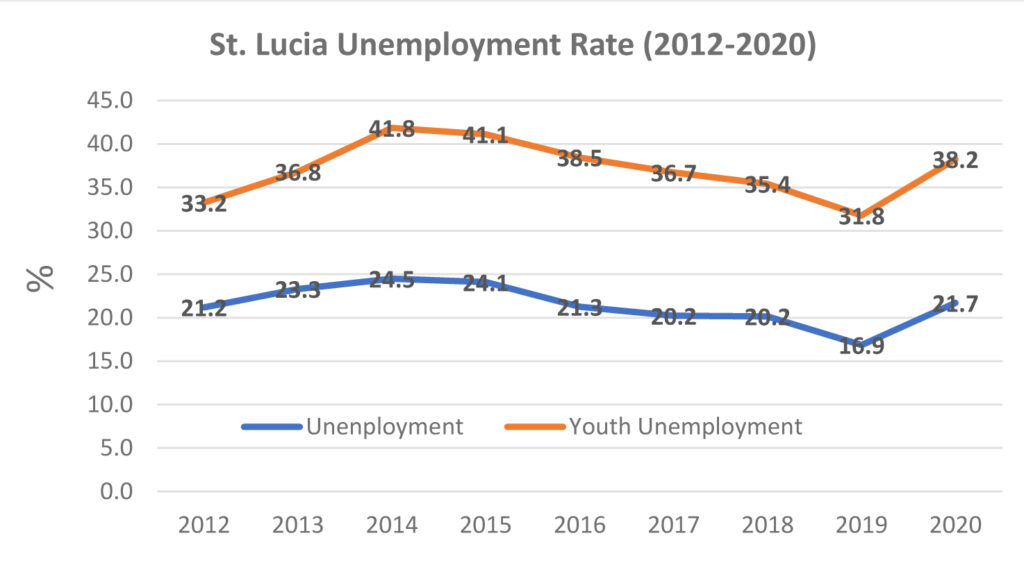

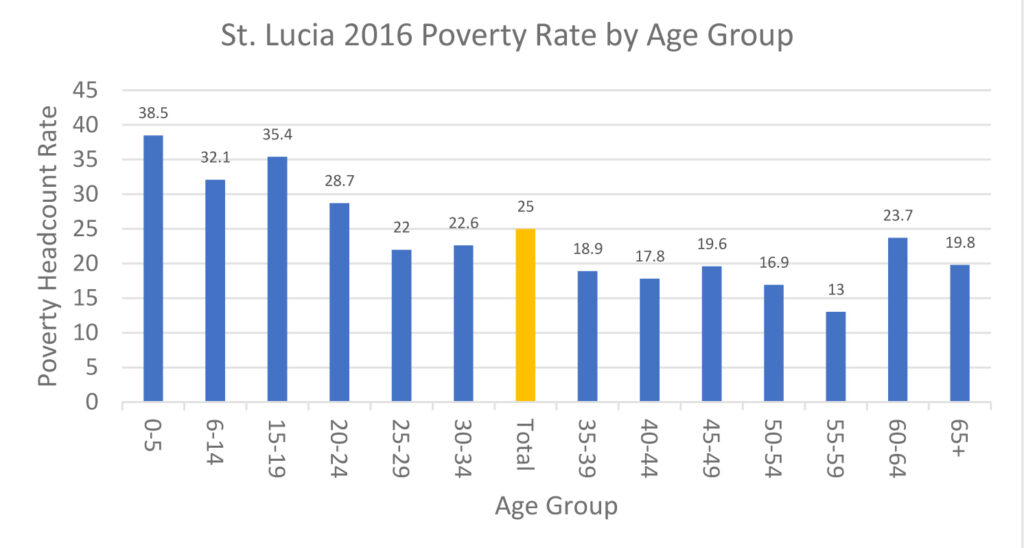

Notwithstanding, the prime minister of St. Lucia, Philip J. Pierre, and the Taiwanese government ought to be applauded for this initiative because a focus on rescuing the youth of the country from economic malaise couldn’t have come too soon. St. Lucia’s youth (15 to 29) unemployment rate for the last five pre-COVID years has averaged about 37%, which meant that over one-third of our youths were jobless but actively seeking employment. Likewise, poverty is common among our youths. In 2016, compared to a national average of 25%, 35% of youths ages 15 to 19 lived in poverty, and so did 29% of those ages 20 to 24.

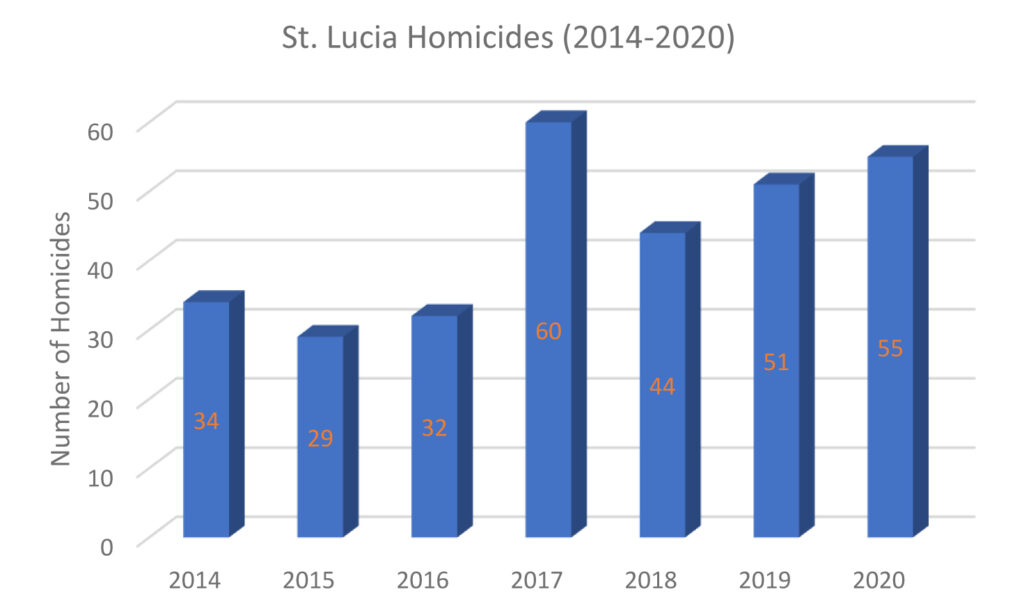

Research has shown that young people are both the “primary victims and perpetrators of crimes in the Caribbean, where about 80% of crimes are committed by persons ages 17 to 29. Therefore, with so many of our youths unemployed and living in poverty, it should surprise no one that crime has become one of the country’s most serious problems. Over the 2010-2019 period, St. Lucia registered about 40 murders per year, corresponding to a homicide rate of 23.2 murders (per 100k population), which was more than twice that of Barbados and more than quadruple that of the U.S. In a study (based on 2018 data) evaluating crime and safety in Barbados and the six independent Eastern Caribbean states, St. Lucia ranked third in murder rate and sexual assaults and first in robberies.

Often we wait and see what plans the government have for our community. At election time we ask, and rightly so, what vision would-be district reps have for the constituencies they wish to represent. But who better can craft a meaningful and realistic vision for a community than the people who were born and raised there, who have intimate knowledge of the residents and the layout of the land, who are daily exposed to the problems and deficiencies of the community? Why do we think that simply because people raise their hands for the privilege of representing us that they are better positioned than us to know what’s best for our community? Won’t we be doing ourselves a favor by coming together and developing a vision and a development plan for our community and sharing our vision with the district rep, with the government, impressing upon them what we want for our community. Isn’t the welfare of our children, our environment, our meagre resources, too important to simply leave in the hands of politicians?

From the above discussion, it should have become clear that addressing the economic malaise of our youth must be a key consideration in setting the country on the path of social and economic progress. Thus, any national economic development initiative that fails to embrace the youth of the country is doomed to languish. Rather than leaving it all up to the government, in a series of articles we hope to provide some pointers and highlight some pitfalls that the government should consider in helping to foster the youth economy. This paper is the first installment of the series.

Taking Stock

To begin, we note that many aspects of the Youth Economy, though never called that, have been at play thanks to the initiatives of various government administrations and business and NGO organizations. Therefore, before launching new initiatives we need to take stock of what already exists or what have been implemented in the past.

Under the National Initiative to Create Employment (NICE), the 2011 Kenny Anthony government had implemented a wide range of employment expansion measures geared toward the youth, including apprenticeships and training programs for crop production, small engine boat maintenance, multimedia production, customer service office administration, and beauty therapy; farm labor support whereby unemployed workers were first trained in agricultural works and then offered employment on “dormant, inactive, or underdeveloped farms”; Christmas private sector employment for students; student summer employment; and training for employment in the cruise-ship sector. Besides these measures, the government had hoped to establish a National Job Placement Center, implement a Land Bank Program to engage young persons to work in high value-added agriculture, and also a Business Grants Program to incentivize businesses to provide job skills training to secondary school students. Indeed, given the extensiveness of Dr. Kenny Anthony’s youth unemployment busting measures, he could have just as well labeled his initiative “developing the youth economy.”

In recent years, the island has been blessed with several new training institutions, both private and public, namely Caribbean Hospitality and Tourism Training Institute, National Skills Development Center, Monroe College, and Springboard Training Institute. In addition, a host of apprenticeship/training programs targeting the youth of the country have been established, including The Junior Achievement Program (JA-SLU), St. Lucia Youth Business Trust (SLYBT), National Apprenticeship Program (NAP), Youth Agri-Entrepreneurship Program (YAEP), Hospitality Apprenticeship Program for Youth (H.A.P.Y), and Caribbean Youth Empowerment Program (CYEP).

Established in 1996 by the Chamber of Commerce, the JA-SLU provides primary, secondary, vocational and tertiary school students with hands-on education on entrepreneurship, work readiness, financial literacy, and on how business works. The SLYBT is another Chamber of Commerce mentorship program that helps budding entrepreneurs ages 18 to 35 to acquire the skills and knowledge (and to access the resources) critical for the success of their enterprise.

Established in February 2018, the NAP was a UWP government initiative that matched unemployed youth residing in the south of the island with job vacancies and provided them with targeted job training to facilitate their entry into the job market. The YAEP is a government initiative that started in 2013 aimed at developing young agri-entrepreneurs through training, the adoption of best practices and appropriate technologies, and through access to land and finance.

H.A.P.Y is an undertaking of the St. Lucia Hotel and Tourism Association (SLHTA) that started December 2014 and pairs unemployed youth of 18 to 35 years interested in working in the hospitality and tourism industry with establishments seeking apprentices with the possibility of long-term employment. CYEP is a USAID-funded project that equips vulnerable youth with the “technical, vocational, and life skills needed to develop sustainable livelihoods.” For example, following a CYEP training workshop in Anse La Raye, 18 youths from the district came together to establish Youth Coast Farm under which they produce crops for the local market.

Clearly, these initiatives can be expected to help build the youth economy. However, they reflect a fundamental flaw in how we have gone about addressing the nation’s problems. Our attempted solutions are piecemeal, disjointed, far short of what is required, short-lived, rarely lasting longer than one election cycle because the new incoming administration invariably replaces inherited programs with their own measures, which some cynics will argue allow them to reap full political credit and reward their people with jobs and contracts and themselves with kickbacks.

The Youth Economy boils down to one issue—employment. Apparently, the government’s main focus will be self-employment, for according to the prime minister “The Youth Economy is one step in the pursuit of a dream to create a new economy based on technology, innovation, and entrepreneurship where young businesspeople will be participants and not merely observers.” The initiative is of great merit, for it is both forward or future looking and encourages youths to create their own employment instead of simply relying on the job market. However, we hope that with this much-touted initiative the prime minister will seize the opportunity to break with the past, and, taking a page from universal secondary education, go beyond simply facilitating youth entrepreneurs, and design and implement an action plan that comprehensively resolves our problem of youth unemployment, with self-employment as just one piece of the puzzle.

So then what is the magnitude of the youth employment deficit?

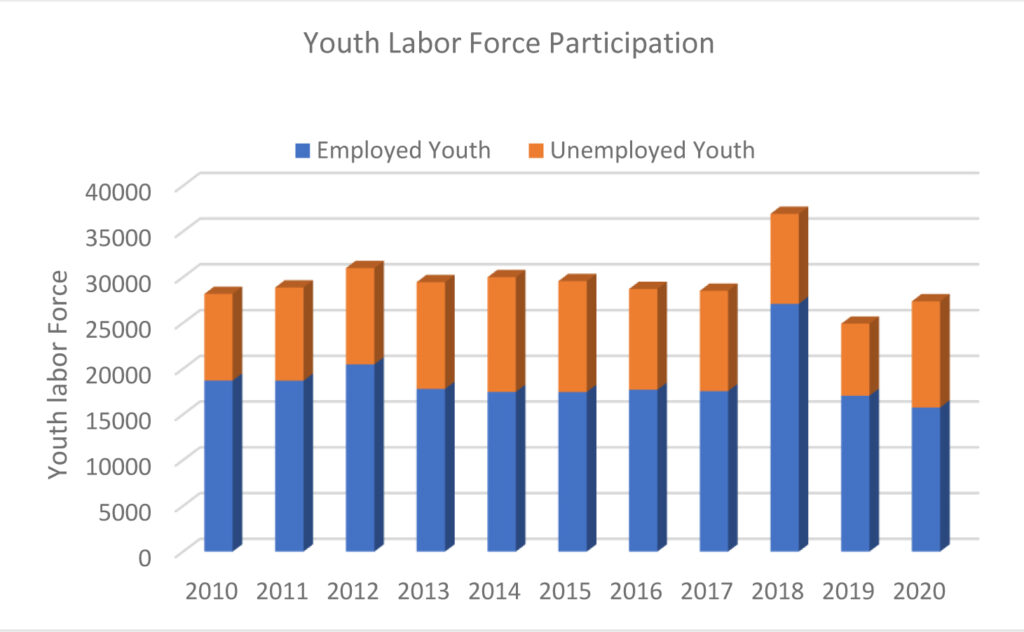

About a quarter (46,655 or 24.4%) of St. Lucia’s 2018 population (178,697) was between the ages of 15 to 29 years, the age group that the department of statistics classifies as the youth population. Over the 2010-2019 period, the youth labor force—youths working or actively looking for work—averaged 29,606 or about 63% of the youth population. This meant that, with an average annual youth unemployment rate of about 36 percent, at any given time there would be about 10,600 jobless youths actively seeking employment. Moreover, with an overall unemployment rate of about 21%, the total number of jobless persons would surpass 17,300.

We should hasten to add, however, that the youth and overall unemployment picture are likely to be worse than what these numbers suggest because the persons whom the unemployment calculations classify as unemployed must be both out of work and seeking employment. Jobless persons who have stopped looking for work do not enter the computations, but for a more realistic picture they ought to be.

As alluded to in No Man’s Land: A Political Introspection of St. Lucia, A comprehensive approach to resolving our unemployment problem and to building the youth economy will use the country’s unemployment statistics such as presented above and including the growth, composition, education, and skills of the labor force, and the number and category of workers each sector employs to determine how many new jobs and the different types of jobs that need to be created to bring the economy to full employment, and then determine the size and configuration of enterprises—self-employment, hotels, manufacturing, informatics enterprises, silicon-like valleys, agricultural and food processing enterprises, etc., —that could accomplish that goal. Armed with this intelligence, government can then formulate strategies and incentive regimes and execute plans of action to make full employment a reality.

In St. Lucia, we have a minimalist attitude that is limiting our ability to excel and to be competitive. There is a tendency to put in the least amount of effort, to use the least quantity and quality of inputs, and to pay the least attention to detail as would just barely get the job done. “That’s good enough;” “we don’t have, so that’s the best we can do;” “that’s just the way things are in Lucia,” seem to be our modus operandi and maybe our excuse for mediocrity. So understandably quality suffers. For example, not long after construction, toilets refuse to work, faucets fall apart, walls crack, roads disintegrate. No matter there is plenty of space, bridges and roads are built large enough to just barely allow two vehicles to squeeze through. This mentality of cutting corners, cheating on resources, half measures, stop-gaps, pervades the whole society.

The doubling of WASCO’s water rates brings no corresponding improvement in the reliability of its water supply, yet LUCELEC was able to turn the corner decades ago and provide a satisfactory power service. One enters an office, government or business, seeking information, and it is as if the people there operate under a principle that they should give the least amount of information as possible, as if every shred of information costs a million dollars.

One can well understand that this kind of mentality arose out of a condition of impoverishment in which as a matter of survival we were forced to economize, to stretch resources as far as possible, even if at the expense of quality. After all, even today, a large percentage of the population is still inadequately housed and faces degrading living conditions. Yet if the country has to improve its global competitiveness, if it has to do right by its youths, it must shift away from this minimalist attitude and adopt a mindset of doing the best work possible with given time and material resources, of dimensioning the task at hand to ensure its comprehensive fulfillment, aiming for the ideal and seeking the resources to realize the ideal.

For the Youth Economy initiative to make a significant and lasting difference, it can’t simply be about establishing a new hotel or a call center that creates a few hundred jobs and that allow us to tell voters we have delivered on our promise to create employment. Nor can it be just about implementing a job training program here and there that allows us to pat ourselves on the back—job well done. Nor just some programs to enable youth entrepreneurial activities. It must depart from our minimalist attitude, the notion of “that’s the most our resources will allow”, or of just being able to do something.

It must be about taking full stock of our employment and economic situation, and devising a dedicated, comprehensive, concerted long-term plan of action that spans administrations and is invariant to them—plan of actions with stipulated achievement targets (number of jobs to be created) and timeframes by which targets are to be met. For example, if we discern that 10,000 new jobs will eliminate our joblessness, and going forward about 500 new jobs per year will keep the economy at full employment, then let us dimension or engineer the economy to create about 2,500 to 3000 additional jobs per year for the next five years.

Our inability to resolve our youth unemployment problem is not so much a matter of limited resources, or lack of relevant data, or lack of know-how, but more a matter of will and desire. As hinted above, we have the requisite data and know-how and it is well within our capabilities to devise strategies and a plan of action and to garner the requisite resources.

Authors

Alexander Clarke is a business innovator and the founder and CEO of MSOLE. Dr. Anderson Reynolds is an economist and an award-winning author of five books. He is considered one of St. Lucia’s most prominent and prolific writers and a foremost authority on its socioeconomic history.

Related Links

Biography of Dr. Anderson Reynolds

Watch NO MAN’S LAND book trailer

Buy Dr. Reynolds Books Online

Buy Dr. Reynolds Books in St. Lucia

Recent Blogs

The Fear of COVID Vaccines

Aftermath: A Provocative Post-Election Analysis of St. Lucian Politics

Chastanet a Blessing in Disguise

![]()